When Unhappy Customers Strike Back on the Internet

Companies need to understand and manage the rising threat of online public complaining. There is ample incentive, because the best ways to respond, and to prevent complaints from recurring, apply not just to the Internet.

Topics

Social Business

The YouTube video that Dave Carroll made about his experience with United Air Lines has already been viewed over 9 million times.

Image courtesy of YouTube.

When customers believe that a company has treated them badly, they may take public action aimed at hurting it. Consider Dave Carroll, a musician who discovered that his $3,500 Taylor guitar was damaged — its neck had been broken — during baggage handling on a United Air Lines flight. At first he alerted several of the airline’s employees at the arrival airport, but none of them had authority to handle his complaint; moreover, they gave Carroll no guidance on how to proceed. Thus began nine months of running the company’s customer service gauntlet. Repeatedly passed from one person to the next, Carroll was finally informed that he was ineligible for any compensation.

Frustrated, angered and feeling that he’d exhausted all customer service options, Carroll wrote a song about his experience and also created a music video, which he posted on YouTube in mid-2009.1 The lyrics included the verse “I should have flown with someone else, or gone by car, because United breaks guitars.” The video amassed 150,000 views within one day, five million by a month later and at this writing more than nine million. The story of the song’s success and the public relations humiliation for United Air Lines was reported in media all over the world. Finally, United offered to compensate Carroll for the damage and promised to reexamine its policies.

The Leading Question

How should companies respond to, or prevent, irate customers’ online public complaints?

Findings

- “A double deviation” — the initial failure followed by failed resolution attempts — is usually critical.

- Perceived betrayal (as opposed to dissatisfaction) drives potential online complainers to act.

- The company’s attempt at recovery should be swift and its apology perceived as sincere.

Another video recently making the e-mail forwarding rounds of the Internet featured an unhappy consumer who happened to be a U.S. marine based in Iraq. Dressed in combat fatigues out in the desert and holding his machine gun, he tells the viewer how Hewlett-Packard demanded to be paid to tell him how to fix his inoperable HP printer. He then aims his weapon and shoots the printer to pieces.2

Admittedly, not every unhappy customer has the wish or the wherewithal to make such graphic statements for a mass audience, but online public complaining does happen every day in diverse forms and varying intensities. The demand is great enough, in fact, that an array of third-party organizations offers preformatted online platforms for customers’ convenience. For example, complaint websites (such as complaints.com and ripoffreport.com), as well as the sites of consumer organizations (bbb.com and consumeraffairs.com), provide online environments in which customers can post their misadventures as well as compare notes with other people. More general user-generated-content websites such as YouTube, Twitter and Facebook also offer venues for complaining, and there are also specifically targeted anti-corporation websites such as starbucked.com.3 Given these and other Internet options, companies whose unhappy customers decide to take revenge can suffer serious consequences. Whereas until a few years ago the damage of negative word of mouth was limited to a fairly small audience, now online reports can go viral, reach millions of people within a short period of time and tarnish a company’s brand.

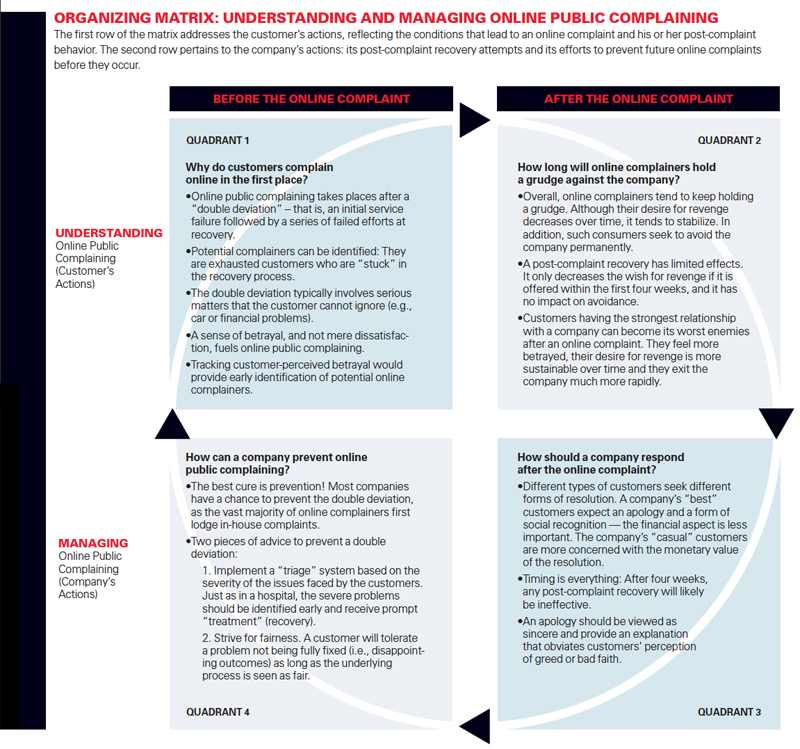

What can companies do, whether in reacting to such negative publicity or in preventing its occurrence? Based on our research, we have developed an “organizing matrix” for these purposes. (See “Organizing Matrix: Understanding and Managing Online Public Complaining.”) The two rows of this matrix reflect our understanding of the behaviors of online complainers (Row 1), which serves as the foundation of our recommendations for managing that behavior (Row 2). The two columns of the matrix reflect the temporal dimension — that is, before and after the online complaint. In other words, the matrix is designed to help companies formulate appropriate tactics both in prevention and resolution modes, as further developed below.

Organizing Matrix

The matrix (read in a clockwise manner) answers the following questions:

Quadrant 1: Why do customers complain online in the first place?

Quadrant 2: How long will online complainers hold a grudge against the company?

Quadrant 3: How should a company respond after the online complaint?

Quadrant 4: How can a company prevent online complaining?

Quadrant 1: Why Do Customers Complain Online in the First Place?

In order to respond to or prevent online public complaining, one first needs to understand why customers pursue that course. That is, what are the triggers? We find that customers go online because (1) they are victims of a “double deviation” and (2) they feel betrayed.

Online Public Complaining Almost Always Follows a “Double Deviation” Most online complainers have been victims not only of a product or service failure (referred to simply as a “service failure” for the rest of this article) but also of a series of failed resolution attempts. In the first case, a product might not have performed as expected, an employee may have been rude or an unanticipated cost, such as a hidden fee, may have been levied. After this initial failure, customers’ attempts to resolve the issue — by complaining in-house to the company’s customer service representatives, managers or owners — may also have come to naught from the customer’s point of view. When such a sequence occurs, customers feel twice violated: First, the company deviated from acceptable practice, and then it deviated again by not satisfactorily addressing the problem. Such “double deviations” can provoke, in effect, a moment of truth for the customer, when the individual concludes that the company does not care about his or her patronage.4

Our research shows that online public complaining is almost always preceded by double deviations. Specifically, after codifying and analyzing 431 online complaints posted to ripoffreport.com and consumeraffairs.com, we found that approximately 96% of the online complaints followed a double deviation.5 Only 4% of the online complaints posted publicly followed a simple service failure.

That is good news for companies because online complainers are not necessarily terrorism-minded individuals who go online at the slightest provocation to impede commercial operations. Instead, they are simply exhausted customers who kept complaining about a serious issue that the company kept failing to address. That is exactly what happened in Dave Carroll’s case.

In general, we are not talking about mild failures involving modestly unpleasant encounters at, say, a restaurant or hotel, which have been the most frequent contexts studied. Rather, we consider severe service failures that the customers simply cannot ignore and for which they need to achieve resolution … or, if all else fails, to go online in some dramatic fashion, as the U.S. marine did. Based on our codification of the online complaints we studied, the most common contexts for such complaints appear to be automotive (11%); large retail purchases (10.5%); credit, debt and mortgage services (10.3%); cell phone providers (9.5%); websites and online services (6.3%); appliances (5.3%); and computers (5%).

Betrayal (as Opposed to Mere Dissatisfaction) Drives Online Complainers Not all customers who are victims of double deviations make online complaints. What distinguishes those who do invest the requisite time and energy, knowing that their chances of material gain are limited? We find that they do so because they feel betrayed by the company — they believe that the product or service provider has violated the norms of a customer-company relationship.6 In a double-deviation context, customers can see betrayal because they believe the company is morally obligated to help them resolve a difficulty that the company itself caused (e.g., Dave Carroll’s broken guitar), and this belief is violated when the company keeps failing them (his nine months of fruitless attempts at resolution). This sense of betrayal motivates customers to take all possible means to “get even.” Indeed, when they feel betrayed, customers see online public action as justified — even noble, as it may, for example, provide warning to other customers.

It is important to note that betrayal is not simply a case of extreme dissatisfaction. Unlike dissatisfaction, betrayal is associated with anger, which is a strong negative emotion that motivates customers to respond strongly. In contrast, dissatisfaction is related to frustration and annoyance, two relatively mild negative emotions that tend to be short-lived and result in more passive actions, if any at all, such as exiting the relationship. But feelings of betrayal can lead customers to persist in their demands for reparation and, if that fails to satisfy, to engage in vengeful behaviors, such as online public complaining, against a company.

Quadrant 2: How Long Will Online Complainers Hold a Grudge Against the Company?

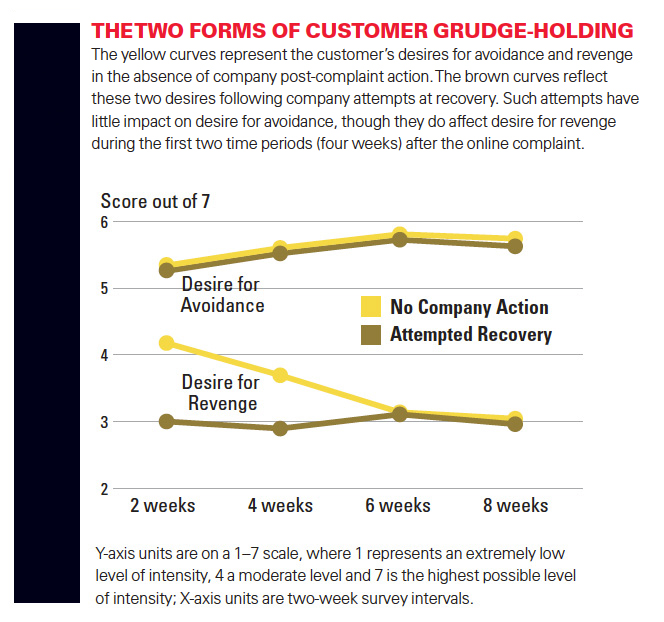

We examined two forms of grudge-holding: seeking revenge and avoiding the company by not returning with one’s business. We found that after customers had complained online, their desire for revenge dropped in the succeeding four weeks and then stabilized, though never disappearing entirely (at least, not up to eight weeks after the complaint — the point at which we last surveyed them). Moreover, customers’ desire for avoidance rose after their online complaint and then remained essentially constant. (See “The Two Forms of Customer Grudge-Holding.”) Thus, we found that customers do continue to hold a grudge: Although their desire for revenge diminishes, they are not coming back.

The Two Forms Of Customer Grudge-holding

Is a Post-Complaint Recovery Possible in an Online Context? But what if a company were to offer some kind of resolution, after the complaint had been posted online, to try to recover its relationship with the customer? In our survey, we found that 27% of the companies made just such a gesture. But it didn’t always help. Customers who received a satisfactory resolution within four weeks after their online complaint reported reductions in their desire for revenge; but resolution offered after that time frame had no impact. It was too late! In any case, such a post-complaint recovery attempt did not seem to bring back the business of the online complainer; it had no significant effect, during any time frame, on the ex-customer’s desire for avoidance. (See the yellow and green curves of “The Two Forms of Customer Grudge-Holding.”) Thus, while a post-complaint recovery attempt may stop the vengeful actions of some complainers, as long as it’s done expeditiously, they are no more likely to return as customers.

Do Certain Customers Hold Grudges for a Longer Time? Every company has its “best” customers — those who bring repeat business, show brand loyalty and in the extreme have strong emotional ties to the company. Other customers – who may make purchases only once or sporadically, have lesser loyalty and have limited bonding with the company – we call “casual” customers.

Does type of customer matter in the context of online public complaining? That is, do a company’s best customers become its worst enemies, or are they more forgiving than casual customers? On the one hand, after a service failure the best customers may give the company the benefit of the doubt, perhaps feel grateful for prior service, or even expect to continue receiving good service in the future. If so, they should be more motivated to forgive the company and might not hold a grudge over time. On the other hand, because the best customers may expect special treatment, when they receive bad service instead they are more surprised and shocked. Having felt entitled to more, when they don’t get it they may feel betrayed all the more acutely.

So, which is it: Are the best customers more forgiving or more vindictive? The data from our study are clear: A company’s best customers are the most likely to become its worst enemies in an online context — at least, in the absence of a proper recovery attempt, about which we will have more to say below. Compared with casual customers, the best customers feel more betrayed, which makes them much more persistent and vengeful in their complaining efforts. And not only do the best customers maintain a greater desire for revenge over time, they also seek to exit their relationship with the company much sooner than do casual customers.

Quadrant 3: How Should a Company Respond After the Online Complaint?

Now we turn to the “managing” part of our matrix. As in their other commercial activities, companies should be methodical when trying to recover their relationship with a customer after his or her online complaint. That is, they should craft their recovery attempts by: (1) accounting for the type of customer (based on the prior relationship); (2) timing the response; and (3) carefully selecting the content of the apology.

Tailoring the Response to the Customer The post-complaint recovery depends on the type of customer involved. Our research shows that the best (relationship-focused) customers are more amenable to recovery efforts, regardless of the recovery’s size or monetary value, than are casual customers. For the best customers, the company’s admission of wrongdoing and the perceived sincerity of its apology could be more important than restitution. As the old saying goes, “It is the thought that counts.” In other words, for those steady customers who value a relationship with the company, recovery may take only a statement of contrition and a symbolic financial act, which communicate that the company values the relationship as well.7

Regardless of the content of the recovery, companies should pay special attention to their best customers because they not only are most amenable to sincere recovery attempts but also are generally the biggest spenders and feel most betrayed after a double deviation. At the same time, companies don’t want customers to feel that they are so big that they are indispensable. One determinant of whether people will act on their desires for revenge is the power they believe they wield to exact such revenge and get away with it.8 Therefore, it is important for managers to achieve balance — to make their best customers feel special without making them feel too special.

For casual customers, the situation is different. Not necessarily interested in affirming their relationship with the company, they may be less won over by evidence that the company values the relationship with them. Instead, such customers typically care only about financial repayment, with the size of the monetary compensation being most important to them.

These results suggest that companies’ responses should depend on what kind of customer experienced poor treatment. However, two points remain. First, companies should not expect that all of these customers are coming back; many are likely to be irretrievably going away. Keep in mind, though, that getting avenging customers to go away can be good riddance, if not good short-term business. Second, giving restitution to all customers who complain on the Internet could in the long run be counterproductive. That is, if companies rewarded customers for complaining online, then eventually even more, not fewer, customers might do so.

Whatever You Do, Do It Quickly Many companies now instruct employees to search the Internet for complaints so as to react swiftly and judiciously, thereby reducing the likelihood of a toxic aftermath. For example, a feature article in the Wall Street Journal detailed how hotels search online for complaints. A major aim is to identify complainers who still are staying at the hotel and to have employees resolve the matter immediately, if possible, but at least before the guest checks out. For example, one guest posted on Twitter that he had “the crappiest room in the hotel,” only to receive within a few hours a note of apology slipped under his door that also offered him a better room.9

In any case, as discussed earlier, there is little point in responding beyond four weeks after the online complaint, as apologies and restitutions will then have very little impact on complainers’ passion for revenge and avoidance.

What to Include in an Apology After the Online Complaint Common experience suggests, as do psychological and marketing research, that for most customers to feel betrayed following a service failure, and to become sufficiently angry to seek revenge, they have to blame the company for what has happened. How much blame customers assign depends on their inferences regarding the nature of the company’s service failure: Was the failure intentional and motivated by greed? Was the failure intentional but motivated by kindness? Or was the failure unintentional? Obviously, inferences of greed lead to more anger than do inferences of lack of motive, and inferences of kindness lead to even less anger. But how critical are such inferences?

We ran an experiment to find out.10 As expected, participants who were presented with the negative motive had a significantly greater desire for revenge than for reconciliation, participants who were presented with no motive had nearly equal desires for revenge and reconciliation, and participants who were presented with the positive motive had a much lower desire for revenge than for reconciliation. Further analysis of the experiment’s and a survey’s results showed that inference of motive was the key belief that drove anger and any consequent desires for revenge or reconciliation.

It thus makes sense that the apology should include a statement aimed at making customers’ worst-case inferences (of greed) unlikely. For instance, airlines’ apologies for delayed or canceled flights should include statements that explain the underlying motives. It’s not, say, that the airline wanted to combine two flights to the same destination because each one was less than half full (a negative inference of greed); it was concerned enough about a plane’s mechanical problem that it canceled the flight to keep passengers safe (a positive inference of looking out for customers’ safety).

Note that simply providing no information about the reasons behind the failure does not help customers rule out worst-case inferences. Faced with ambiguity, people tend to err on the sinister side when inventing explanations. That is, in the absence of information, customers don’t necessarily come to a neutral “I don’t know”; they often connect dots that perhaps should not be connected and become convinced that the company is just plain greedy. Don’t allow customers to go down this road; give them an explanation instead.

Other research on apologies suggests additional elements that need to be included.11 First, apologies should be sincere and truthful. An insincere apology can be worse than no apology at all. Second, effective apologies are not about the company assigning blame elsewhere. Doing so can actually backfire, at least when it’s clear to the customer that the service failure was caused by the company’s own negligence or incompetence.

Not assigning blame at all in an apology may not be any safer either. Consider the research on doctors’ apologies to patients.12 Many doctors will not apologize when they make medical mistakes out of fear that such admissions of guilt could result in malpractice lawsuits. The research, however, suggests that these doctors have it backward; in reality, patients are more likely to sue for malpractice when they receive no apology or an insincere apology. That is why some states have recently passed “I’m sorry” laws that allow physicians to admit to a mistake without it being used against them in court.

Basically, we advise companies to own up to honest mistakes when they make them and not to let the customer believe that they are motivated by greed.

Quadrant 4: How Can a Company Prevent Online Public Complaining?

Even better is to respond so quickly after the initial service failure that the second element of the double deviation does not occur, with the result that most customers do not complain publicly and online. Good prevention, after all, is usually preferable to a good cure. In that spirit, we recommend that companies design their recovery efforts (1) based on a triage system and (2) by focusing on the process and not just the outcomes.

Develop a Triage System. Clearly, different customers often need to be handled differently. For that reason we suggest that companies, in pursuing recovery processes, emulate the triage that doctors perform during medical emergencies involving multiple casualties.13 For example, in a natural disaster where injuries are many but medical resources are few, physicians must decide who to treat immediately, who can wait for treatment and who will receive no treatment at all. The main principle that guides triage is to first treat the most life-threatening injuries of people who can be saved, second the non-life-threatening injuries and last the life-threatening injuries of people who cannot be saved.

Service failures are analogous to such medical situations in three ways. First, companies have limited financial and human resources to deal with service failures, much as aid stations in natural disasters have limited medical supplies and physicians to treat multiple patients. Second, not all customers can be “saved” — that is, recovered — just as not all patients can be saved. And third, some service failures, being more threatening to the customer and to the customer-company relationship, are more likely to motivate the customer to seek revenge against the company, just as some injuries are more severe than others and carry greater risks of suffering and death.

This analogy suggests some recommendations. Companies should identify those —customers who have suffered the most severe service failures and who can also be recovered. Fortunately, such identification should be relatively easy, given that the most recoverable customers are typically a company’s best customers. Moreover, like severely injured patients who can be healed, these customers should be attended to very quickly. Wait too long — some four weeks or more — and the chances of recovering them drop steeply.

The Process Matters More than the Outcomes. We describe this commercial version of triage as preventive, not just curative, because it should be performed before the second element (recovery failure) of the double deviation occurs. More preventive still, perhaps, is a system in which customers may not mind service failures so much because they perceive a fair process for complaining about them. In fact, the “fair process effect” — a well-known psychological phenomenon, particularly in labor-management settings — demonstrates that employees will tolerate disappointing outcomes as long as they perceive the decision-making processes surrounding these outcomes to be fair. In other words, for employees to become very angry and challenging, they have to believe that both the outcome and process are unfair.

In our research, we have found that the fair-process effect may apply in the consumer setting as well. Specifically, we have measured how the perception of fairness of the systems that companies put into place to address complaints — systems characterized by parameters such as voice, control, speed, waiting time and flexibility — can substantially reduce customers’ sense of betrayal. Thus, as long as the company uses such fair processes, and as long as it makes customers aware of them, customers will tolerate the occasional service failure.

Comments (4)

Kapil Sopory

Siswanto Gatot

Andrew McFarland

RalfLippold